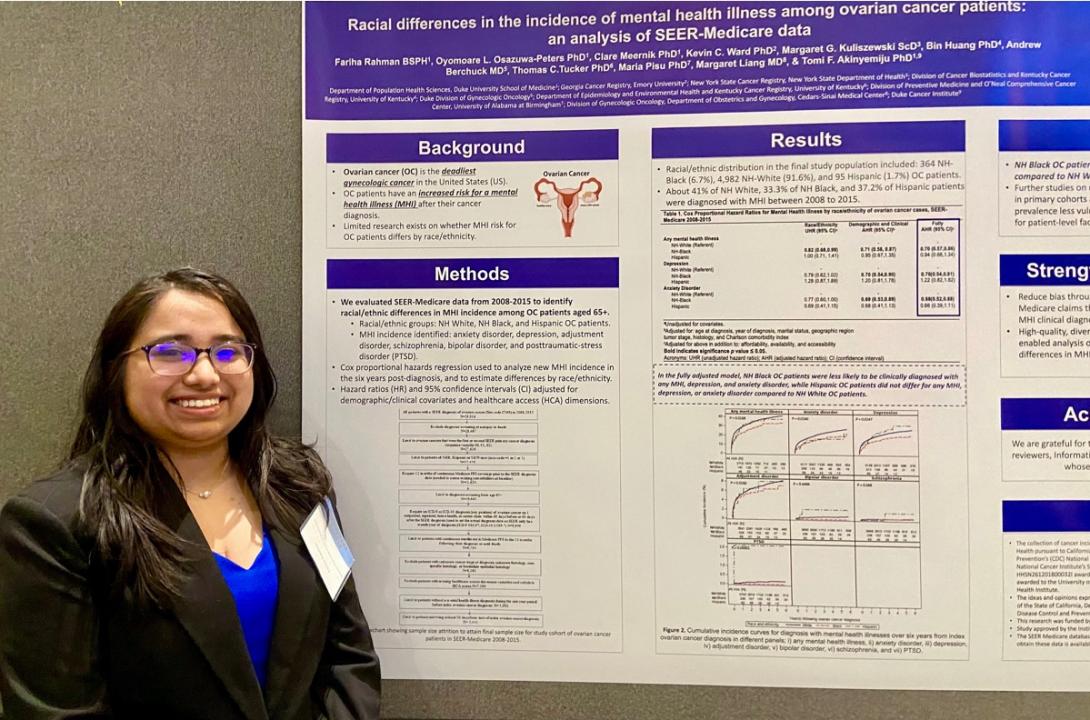

Exerpts from a DCI interview: "My project looked at the racial differences and incidence of mental health illness among the ovarian cancer patients. And we specifically analyzed the SEER Medicare dataset, which is a data set from the National Cancer Institute...First a little background: Ovarian cancer is considered one of the deadliest cancers of the female reproductive system in the United States. There has been studies that have shown that these patients are at increased risk for mental health illness, but there hasn't been much research on whether this risk differs by race and ethnicity. It's really important to actually look whether it differs because research has shown that in terms of prognosis and survival non-Hispanic Black individuals are at a greater risk than non-Hispanic white individuals. It's been attributed to a lot of different factors — social determinants of health, systemic racism, provider bias, affordability, accessibility...

It's important to consider both the mental state of an individual in addition to the physical state, so that's why our study in particular focused on mental health. Overall we analyzed a dataset that was over 5,441 pages (Medicare claims data) And in this study itself, we were able to analyze mental health illness incidence for depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, adjustment disorder and PTSD for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic ovarian cancer patients.

The main finding from the study... was that non-Hispanic Black American cancer patients were less likely to receive a clinical diagnosis of a mental health illness, for depression or anxiety disorder, and this is really significant because psychiatric literature has shown that this population is at a higher risk for under diagnosis... And that's something that's really important to look at because this population is already vulnerable.

Further studies need to really look at the factors in particular... (of why) they are less likely to get mental health care."

Poster co-authors included: Co-authors on the project include Oyomoare L. Osazuwa-Peters, PhD; Clare Meernik, PhD; Keven C. Ward, PhD; Margaret G. Kuliszewski, ScD; Bin Huang, PhD; Andrew Berchuck, MD; Thomas C. Tucker, PhD; Maria Pisu, PhD; Margaret Liang, MD; and Tomi Akinyemiju, PhD.