On Thursday, April 14, 2022, Duke Cancer Institute clinical providers, researchers, staff, and leadership came together to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center (now called Duke Cancer Institute).

As the DCI 50th kickoff celebration was gearing up on the grassy circle in front of Duke Cancer Center building in Durham, a few patients stopped by the adjacent Seese-Thornton Garden of Tranquility for some respite.

A breast cancer patient of Susan Dent, MD, braced for a long day of chemotherapy infusions. A man with stage 3 melanoma, being treated by Brent Hanks, MD, chatted in the shade of a tree with his wife ahead of his next appointment. A woman on her way to the Duke South clinics, meanwhile, shared her worries over her brother’s recent esophageal cancer diagnosis, their strong family history of cancer, and the importance of keeping up with her mammograms.

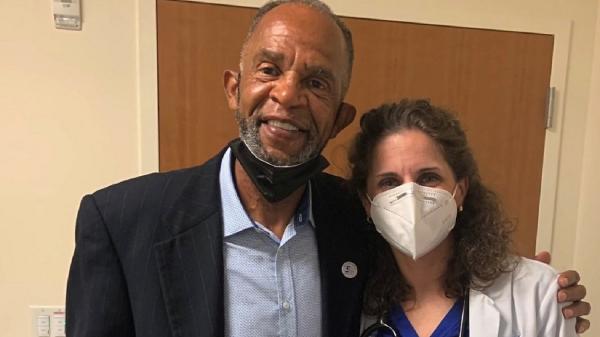

Joe Moore, MD — who hung up his DCI lab coat in 2019 after a 44-year Hematology /Oncology career — was admiring the newly-installed Sound of Hope bell (a gift of the J. Gordon Wright family in honor of Nancy Wright, a pancreatic cancer survivor) before Jana Wagenseller, RN, escorted him across the grass to a front-row seat, stage right. (Moore had begun his medical career at Duke in 1975 as a fellow and Wagenseller had begun her nursing career at Duke in 1976 and served in multiple leadership roles before retiring in 2004).

The Duke University Marching Band made a jubilant entrance onto the green and briefly performed in front of a big-screen slideshow showcasing moments in DCI history before the official program began.