The bacteria in your gut help regulate your immune system. So, can priming them with an over-the-counter probiotic protect against COVID-19?

A Duke Cancer Institute physician-scientist and a critical care specialist are exploring that question, via a clinical study being conducted entirely remotely and made possible by philanthropy.

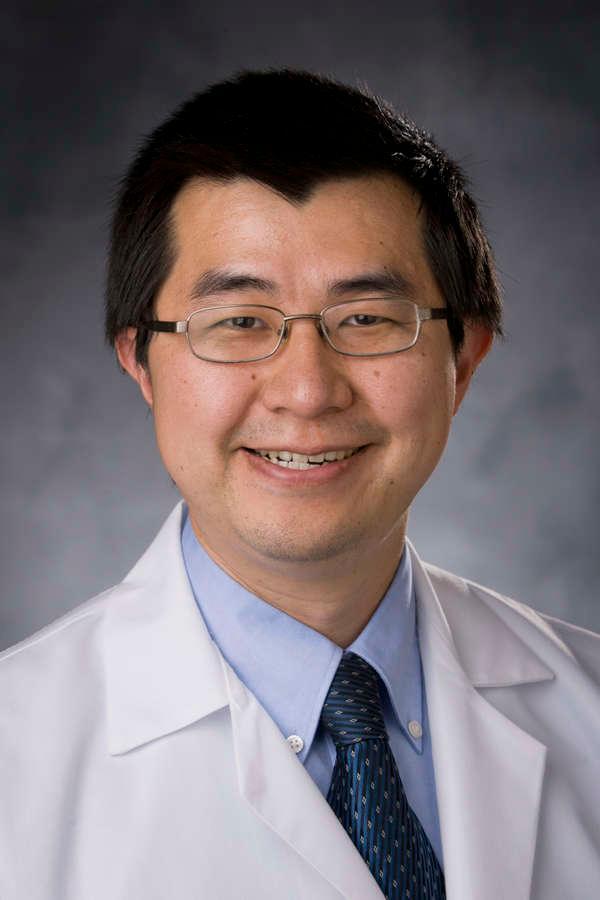

Tony Sung, MD, a stem cell transplant physician and an associate director of the Duke Microbiome Center, has long been interested in the microbiome (the collection of all the bacteria and other microorganisms that live in the human body) because it can influence complications in patients after stem cell transplant, including relapse, survival, and infection.

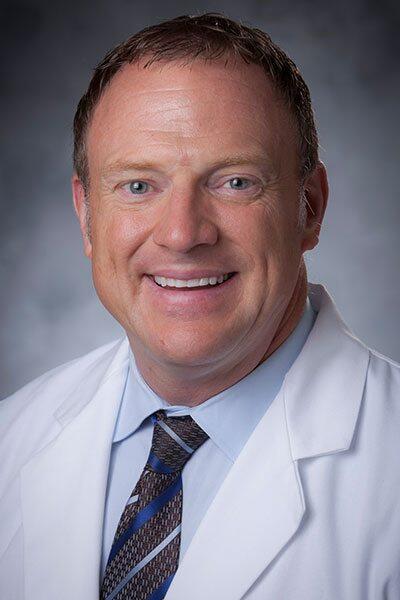

Paul Wischmeyer, MD, professor of anesthesiology and surgery, specializes in enhancing preparation and recovery from surgery and critical care.