Charlotte-area resident Vickie Johnson, 72, was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2018 after seeking care twice for abdominal pain. First, she was diagnosed with appendicitis and had her appendix out. Then, when her pain persisted beyond the recovery period, she received a new diagnosis. A scan at the ER showed a possible tumor. She went back to her appendix surgeon, had the mass in her colon removed, and was referred to a hospital oncologist. He referred her to a second surgeon who performed an even more aggressive surgery to remove all the remaining cancer in her colon and got her started on chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, after each chemotherapy infusion she experienced severe chest pain. As she described it, “terrible spasms like I was having a heart attack.” Her oncologist didn’t have a plan b. “Finally, he said ‘I'm sorry, there's nothing I can do. We'll just test your blood every so often and get a scan every six months,’” Johnson shared. She wasn’t ready to give up, and as it turned out she didn’t need to.

Johnson’s next area oncologist — Justin Favaro, MD, PhD — who'd done his medical training at Duke, brought a cardio-oncologist onboard the care team. The two providers tweaked the chemotherapy regimen she’d been on with the first oncologist; adjusting the dosage so her heart would be able to tolerate it. That worked, but successive treatments didn’t make any headway against her cancer.

Johnson had begun 2019 in treatment for newly diagnosed colon cancer and ended that year with the death of her husband and progression of her cancer. During 2020, she’d endured another chemotherapy regimen but with no success. Cancer metastases remained in her liver and her lungs.

Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who have progressed on standard chemotherapy receive limited benefit from the available standard of care options. Johnson had genomic testing done and it turned out her cancer was hardwired with a KRAS G12C mutation, an alteration found in 3 to 4% of all metastatic colorectal cancer cases. Favaro said there was one more option.

In the summer of 2021, he referred Johnson for enrollment in CodeBreaK 101, an early-stage clinical trial (phase 1b/2) at Duke Cancer Institute testing a new approach to treating KRAS G12C-mutated solid tumor cancers — a new KRAS G12C inhibitor drug (sotorasib) in combination with other anti-cancer therapies of choice, including FDA-approved antibodies, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy drugs. DCI was one of the first institutions worldwide to open this trial, which had launched in December 2019.

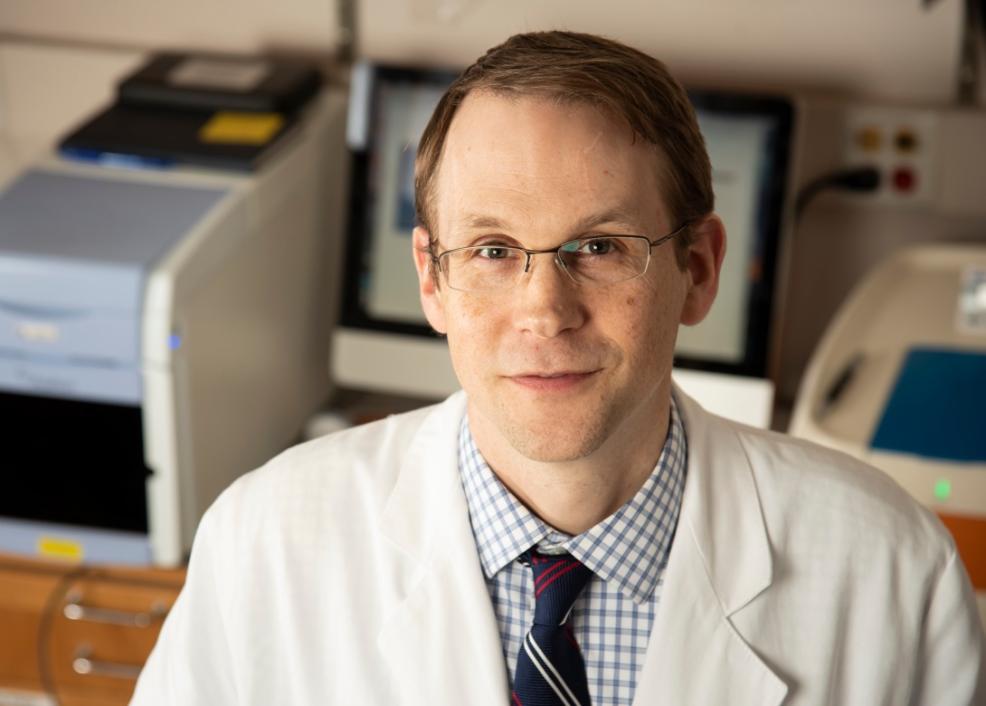

Duke Cancer Institute GI medical oncologist and Associate Professor of Medicine John Strickler, MD, was Duke site principal investigator. Strickler is a colon cancer specialist who co-leads the DCI Precision Cancer Medicine and Investigational Therapeutics Research Program and the Molecular Tumor Board.

Johnson said she had “no hesitation” about her decision and was grateful when she qualified for recruitment to the study under the care of Strickler.

“This was the option. Nothing else was working,” Johnson recalled.