For 27 years, Heather Paradis, MSN, a 1995 graduate of Duke University’s Master of Science in Nursing Program, cared for cancer patients at Duke University Hospital as a hematology-oncology nurse practitioner. As she saw many patients fighting the disease, she had no idea that she would one day be on the other side of cancer care.

What she learned when she visited that other side is now helping others who have been touched by cancer.

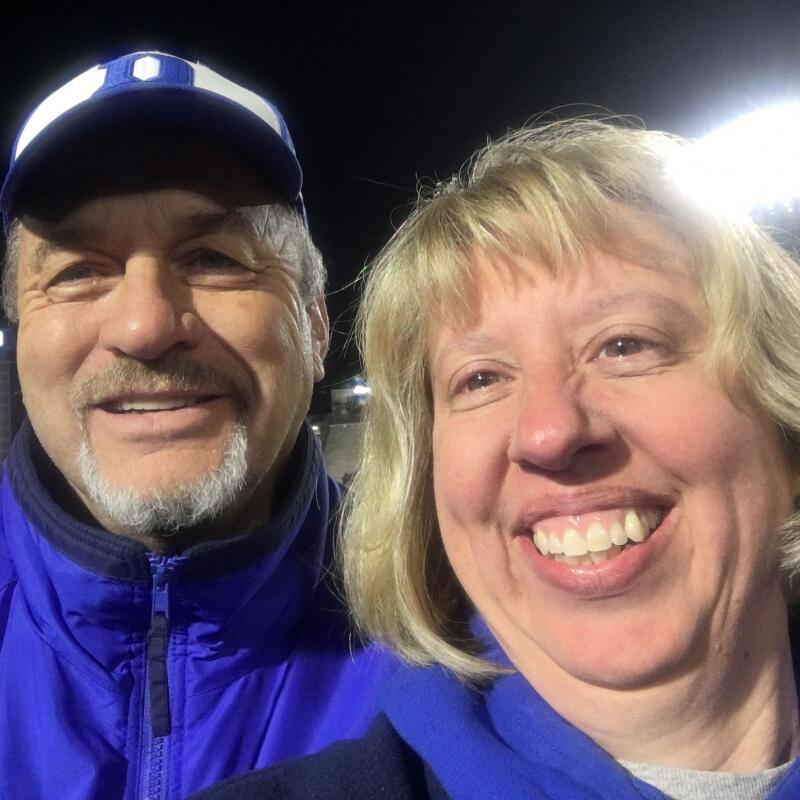

In September 2016, Paradis’ husband of two years, Eric Paradis, went for his annual physical and had routine blood tests. The results indicated an elevated white cell count. “At first we thought it was just a reaction to poison ivy exposure, because Eric had cleared the area on which we started building our new house,” Heather says.