When Duke Cancer Institute Board of Directors Nancy Wright finished chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer, nurses on the fourth floor of Duke Cancer Center brought out a small bell for her to ring to celebrate.

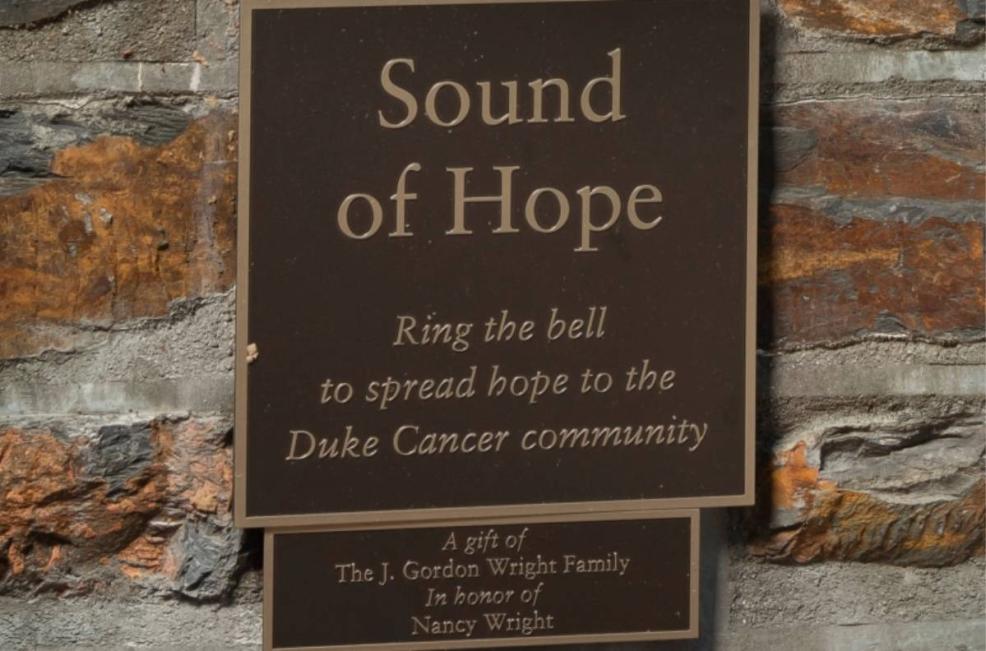

Feeling inspired, Wright’s family, including her husband, J. Gordon Wright, who 10 years ago this year survived stage 4 lymphoma, donated the Sound of Hope Bell in her honor.

The Wrights stopped by the Seese-Thornton Garden of Tranquility across from Duke Cancer Center to Sound of Hope Bell shortly after it was installed in April 2022.

Photo by Les Todd.