When Joseph O. Moore, MD, came to Duke as a fellow in 1975, he and his mentors treated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with a chemotherapy regimen that was like a “wet blanket.” It suppressed the cancer for a few years. “But it didn’t change the trajectory of the disease,” Moore said. Patients developed acute leukemia, which was almost always fatal.

By the early 1990s, younger patients could achieve a cure with a bone marrow transplant, though complications were common. By 1999, Moore was the Duke investigator for a national study of a targeted drug, imatinib, which stops leukemia cells from growing by shutting down a key protein.

When imatinib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001, it transformed CML into a disease easily treated by taking a pill.

When Moore retired from clinical practice in 2019, he was involved in a study following people with CML who had been taking imatinib long term, which showed they could safely stop therapy.

The CML example provides a snapshot of just how far cancer treatment has come in the last 50 years. For many patients, “There’s an expectation of success and people living normal lives,” said Moore, professor emeritus of medicine.

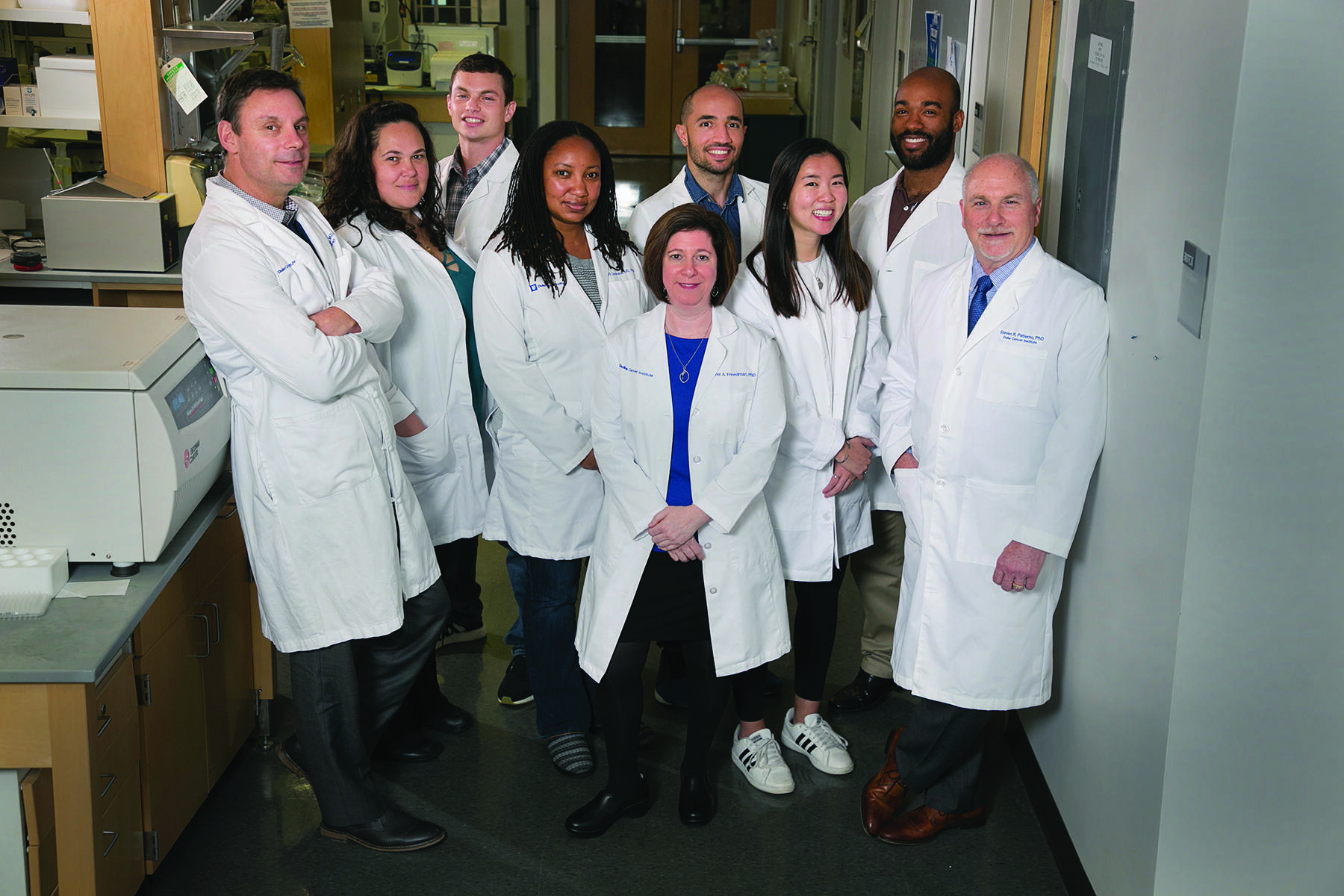

Much of that progress can be traced to research funded by the “war on cancer,” which launched in 1971 when congress passed the National Cancer Act. The act gave the National Cancer Institute (NCI) the authority and funds to create a national cancer program. The backbone is a network of comprehensive cancer centers that provide patient care and conduct rigorous research to find new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer.