Pancreatic Cancer: Facing a Formidable Foe

Published

From the Duke Cancer Institute archives. Content may be out of date.

From the Duke Cancer Institute archives. Content may be out of date.

In February 2016, Tara Wilkes left her job as a decorator and furniture sales associate, locked the door of her second home on Lake Waccamaw and moved back inland to the family home in Rockingham, North Carolina.

“I just couldn’t do my job,” said Wilkes, a petite and active 56-year-old grandmother of four. “I was tired, really tired -- and there was the swelling. I could no longer wear my rings, and my shoulder hurt.”

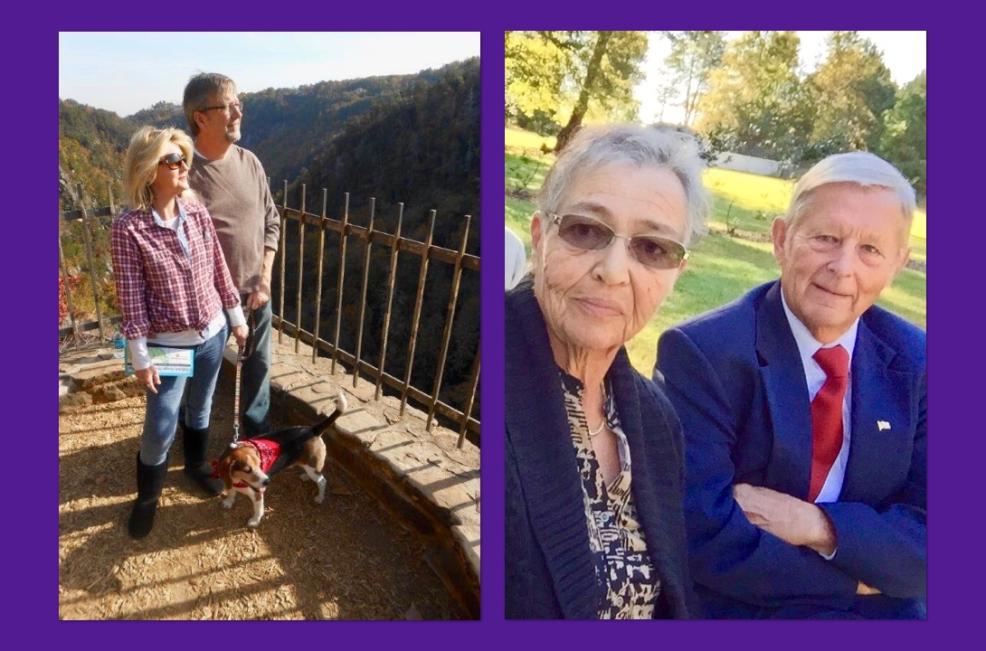

Wilkes had been the picture of health and vitality just a few months before, when she and her husband Neal, a businessman who’s often traveling, got a break from their busy schedules for a hiking getaway in the Georgia mountains.

Wilkes attributed the swelling to walking the 40,000-square-foot showroom, daily, and she figured she’d pulled her rotator cuff carrying heavy fabrics up and down the stairs of her clients’ coastal homes. Her local physician didn’t find anything wrong with her shoulder.

However, a trip to the emergency room when she turned jaundiced while out shopping, led to the eventual discovery of a tumor in her pancreas. An astute doctor connected her shoulder pain to a possible gallbladder problem and ordered an endoscopy — a nonsurgical procedure used to examine the digestive tract. Her gallbladder as it turned out, was indeed damaged, due to the pancreatic tumor nearby pressing against it.

Wilkes was referred to Duke surgeon Sabino Zani Jr., MD, and oncologist Niharika Mettu, MD, PhD. She underwent five-and-a-half weeks of radiation and chemotherapy, and in June that year had the Whipple procedure (a pancreaticoduodenectomy), in which the head of the pancreas is removed along with a portion of the bile duct, gallbladder, and the first portion of the small intestine. After undergoing 12 once-a-week intravenous chemotherapy treatments following surgery, and just in time for Christmas 2016, Wilkes was declared cancer free. Healthy again, she made a photo from that 2015 Georgia hiking trip into that year’s Christmas card.

Climbing the Charts

Located behind the stomach, the pancreas has both endocrine and exocrine functions; making a number of important proteins including insulin and digestive enzymes. Deaths from pancreatic cancer are projected to increase to more than 60,000 per year by 2030, which will make pancreatic cancer the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths after lung cancer.

According to the National Cancer Institute, risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer include smoking, being very overweight, having a personal history of diabetes or chronic pancreatitis, having a family history of pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis, and having certain other hereditary conditions.

At this time, there are no guidelines that recommend pancreatic screening for those who harbor any of the personal medical history related risk factors and no guidelines that recommend pancreatic cancer screening for the general population. There is a consensus at Duke to consider screening patients with familial clusters of pancreatic cancer or those with hereditary genetic mutations that predispose the family to higher rates of pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is a rare, but highly morbid disease, accounting for just 3.2 percent of all new cancer cases, but 7.2 percent of all cancer deaths. The American Cancer Society projected there would be 53,670 new cases in the U.S. in 2017 and 43,090 deaths (final figures are not yet available).

Deaths are projected to increase to more than 60,000 per year by 2030, according to authors of a paper published in Cancer Research, which will make pancreatic cancer the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths after lung cancer — surpassing liver, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers in mortality.

“This rise is, in part, secondary to decreased cancer-related deaths associated with breast, prostate and colorectal cancers but is also due to the aging of the American population,” said Duke Cancer Institute surgical oncologist Dan (Trey) Blazer III, MD.

It’s an aggressive malignancy, noted Blazer, explaining that even in patients where surgical resection is possible, long-term survival is not achieved in the majority of patients, though outcomes have improved over the last decade.

According to the National Cancer Institute, the five-year survival rate for those with advanced disease is less than 10 percent — currently the worst five-year survival rate of all solid-organ malignancies.

“Our ability to cure that cancer is still pretty limited, despite improvements in surgical outcomes and systemic chemotherapy, so as the number of new cases go up, the deaths are going to go up,” said Blazer.

Because most symptoms of pancreatic cancer are non-specific — including weight loss, vague abdominal discomfort, change in stool color or consistency — the majority of pancreatic cancer patients already have advanced or metastatic disease when they are diagnosed. Depending on if they take and respond well to chemotherapy, metastatic patients have an average expected survival of between four months and a year.

A Surgical Option ?

Wilkes was fortunate that her tumor was identified early, explained her physician Mettu, when surgery was still possible. Only about 15 to 20 percent of patients, said Blazer, qualify for surgery. Typically, surgery is an option only if the pancreatic cancer is limited to the pancreas, has not metastasized to other organs and has not locally advanced to the point of encasing local regional blood vessels. However, at Duke and other select centers, in patients who are not surgically resectable by classic criteria, locally ablative therapies such as irreversible electroporation (IRE) may also be used, a novel strategy, said Blazer, to improve the numbers of patients who may be eligible for surgery.

Those who’ve had no form of chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery, have an average survival between 18 and 24 months. There’s a longer average survival — 30 to 35 months — in patients for whom chemotherapy and radiation taken ahead of surgery has either shrunk their tumor or stopped their cancer from progressing.

“You’ll see a definite improvement in those folks,” said Blazer.

However, Blazer explained that surgery doesn’t come without complications. While the operative mortality rate for the most common surgery, the Whipple, is less than two percent at high-volume institutions, including Duke, around 30 to 50 percent of patients will likely have some sort of complication after the procedure, ranging from minor to serious. If the tumor is in the body or tail of the pancreas, then a distal pancreatectomy, in which the pancreas and spleen are removed en bloc, may be an option. That procedure, Blazer said, is “less risky than the Whipple” and is “usually a pretty well tolerated procedure with fewer complications.”

Dolly's Story

Dolly Dunnagan, like Tara Wilkes, didn’t see it coming when she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in September 2014, but jaundice and extreme fatigue warranted a doctor visit. (Neither Dunnagan nor Wilkes had any of the personal risk factors or a family history or genetic connection to the disease.)

While Dunnagan had lost about 10 pounds over the summer, she chalked it up to long hours gardening at the family beach house on Harker’s Island. Then 67 years old, the grandmother of two was surprised by the diagnosis. Standard-of-care radiation and chemotherapy was followed by surgery at Duke in January 2015.

After four months of chemotherapy, Dunnagan was cleared of cancer, but last year a scan showed a couple of suspicious spots on Dolly’s lymph and the cancer antigen levels in her blood began to rise. Biopsies turned up negative.

Dunnagan and her physician Mettu continue close surveillance for her cancer, which consists of labs, imaging, and clinic visits every few months.

“We’re just playing a wait and see game right now,” said Dunnagan, who enjoys fishing on the weekends with her husband of 52 years.

Making Headway

“We’ve made some headway with pancreatic cancer treatment for all stages of pancreatic cancer,” said Mettu, while acknowledging that it’s an uphill climb.

In the last 10 years, several single agents and combinations of chemotherapies have been approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer — that can extend survival from four months up to six, eight, or 11.5 months.

“We’re still talking about improvements in life expectancy, with chemotherapy, measured in incremental numbers of months,” cautioned Mettu, explaining that it’s difficult for drugs to penetrate the organ’s complex microenvironment and kills the cancer cells. “What we need are regimens that are going to lead to responses that are durable, or that last a long time, like in breast cancer. I think the longer I do this, the more I realize that aiming for a cure may not be possible but aiming for long-term disease control is very reasonable.”

Immunotherapies, which are approved for the treatment of several cancers and have led to durable responses in other cancers, have not been shown to work for pancreatic cancer patients, at least as single agents, but studies of treatment regimens that utilize a combination of different checkpoint inhibitors or a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy drugs have been and are currently being conducted, including at Duke.

“Whenever possible, clinical trials are highly recommended for metastatic pancreatic cancer patients, since survival is still not optimal,” explained Mettu. “A good clinical trial is probably better than sticking with standard of care as it will further our understanding of how to treat this terrible disease and help to improve outcomes for patients by improving both quantity and quality of life for patients with pancreatic cancer.”

A Happy Holiday

Tara Wilkes, now a pancreatic cancer survivor, has spent the past year doing what she loves, including going to the beach, taking walks, playing with her grandchildren, visiting elderly shut-ins, restoring furniture, and painting. She painted a giant sunflower onto a barn door on her property, and hand-painted pillows and oven mitts as Christmas gifts for the family and friends that have taken care of her and prayed with her through her cancer “ordeal.” She and her husband Neal hosted a Christmas party at their house this year.

“I’m doing great,”she said. “One of the things that Dr. Mettu said to me, when I was cleared, was that it was time to start living my life again.”

“Both Tara and Dolly have done well, so may well do better than average,” reflected Mettu. “I am always inspired by the optimism of my patients with pancreatic cancer; so many of my patients find the ability to make the best of this situation and are very much invested in helping to further our treatments for this disease by participating in research that will move the needle forward in pancreatic cancer.”

Screening & Pancreatic Cancer (posted on January 2018)

According to the National Cancer Institute, risk factors associated with pancreatic cancer include smoking, being very overweight, having a personal history of diabetes or chronic pancreatitis, having a family history of pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis, and having certain other hereditary conditions.

At this time, there are no guidelines that recommend pancreatic screening for those who harbor any of the personal medical history related risk factors and no guidelines that recommend pancreatic cancer screening for the general population.

Paul Jowell, MBChB, a Duke medical gastroenterologist who specializes in gastrointestinal endoscopy and pancreaticobiliary disorders, said that current screening modalities include minimally invasive procedures, and are relatively expensive. As a result, screening has not been studied in the general population.

“In a screening program, we need a test that will be cost effective at identifying the disease at a stage that will allow us to significantly change the outcome,” said Jowell. “We don’t yet know that screening for pancreas cancer will be effective in significantly improving the outcome. Considering the lack of definitive data on effectiveness of screening as well as the cost and invasive nature of the tests, screening is not currently recommended for the general population.”

While most cases of pancreatic cancer are considered to be sporadic (non-hereditary), approximately 10 percent of pancreatic cancer patients have a familial component. Early data has suggested that screening may be beneficial in these patients and there is a consensus at Duke to consider screening patients with familial clusters of pancreatic cancer or those with hereditary genetic mutations that predispose the family to higher rates of pancreatic cancer.

Alyson McGhan Johnson, MD, a Duke gastroenterology fellow with an interest in pancreatic cancer and interventional endoscopy, presented on “The Who, When, How and What’s New in Pancreatic Cancer Screening” at GI Grand Rounds in November.

Current general guidelines at Duke are to screen individuals with:

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (mutations in STK11, which causes that syndrome)

- Mutations in the FAMN p16/CDKN2A gene (associated with hereditary melanoma)

It is also reasonable to consider screening individuals with:

- A mutation in another gene associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer (e.g. BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, or the genes associated with Lynch syndrome) if there is also a family history of pancreatic cancer.

- A family history of pancreatic cancer involving two first degree relatives (parent, child or sibling) or three 1st, 2nd or 3rd degree relatives (parent, child, sibling, aunt, uncle, grandparent, niece, nephew, first cousin)

The screening protocol at Duke for those high-risk individuals (detailed above) is endoscopic ultrasound alternating with an MRI or CT scan every six months, said Jowell. For most at high risk, the screening is started at age 50 or at least 10 years before the youngest age of a family member that had pancreatic cancer.

“Patients considered for possible screening should first be seen in the Hereditary Cancer Clinic because they have genetic counselors who take a careful family history and order appropriate genetic testing if needed,” said Jowell. “These clinicians can help assess the genetic risk factors for the individual.”

It is possible to identify pre-cancerous lesions on the MRI and or the endoscopic ultrasound, said Jowell.

“There are several features we look for and if the clinical suspicion is high, we can biopsy abnormal areas and if indicated refer for surgical removal, particularly in a high-risk patient,” he explained.

Findings from a new study, funded in part by NCI, suggest that a less invasive test — a blood test in the early stages of development — may be able to accurately detect pancreatic cancer at its earliest stages, when it is most likely to respond to treatment.

“If a more simple screening test such as a blood test is proven to be effective for screening, this could be a game changer especially if cost is not prohibitive, but we currently don’t have such a test,” said Jowell.

Patient Updates

UPDATE JUNE 2019: Ms. Dolly Dunnagan, passed away on Friday, June 28, 2019, at her home. She was 71.

UPDATE OCTOBER 17, 2021: Dr. Mettu reached out to share some good news about Ms. Tara Wilkes. “You had previously written about Ms. Tara Wilkes in 2018. She is now five years out from completing her therapy for pancreatic cancer and is disease-free, and what we would consider cured.” The only drug that Ms. Wilkes, now 60, had regularly taken over the past five years was Vitamin D and Calcium. She and her husband Neal are celebrating the milestone of reaching "that magic number 5" and remain committed to spreading the word about pancreatic cancer. Over the past few years they've been camping and we spend time with the grandchildren, and doing a lot of yardwork. (READ the new article "That Magic Number 5")